Exploring the Scientific Design of a 2-Dimensional World

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to the 2-Dimensional World

Imagine a universe that exists solely in two dimensions. This thought may seem far-fetched, yet there is a scientific basis for contemplating life in such a realm. While we inhabit a three-dimensional environment (or four if we include time), envisioning existence within a flat, two-dimensional plane can be challenging, if not downright absurd.

Could life genuinely thrive in a two-dimensional setting? This inquiry goes beyond mere science fiction. We can actually conceptualize a scientifically plausible two-dimensional world, complete with its own laws of physics, chemistry, biology, and more. As we delve into this topic, we will uncover significant insights that arise from such an imaginative exploration.

The Historical Context of the 2-Dimensional Concept

The notion of a two-dimensional universe was first introduced by Edwin Abbott Abbott in his 1884 satirical novel "Flatland." While Abbott's work mainly approached the subject from a fictional perspective, Charles Howard Hinton later contributed to the scientific framework with "An Episode of Flatland" in 1907, where he introduced cardboard characters and the initial scientific principles governing a flat world.

Hinton's work faded into obscurity until Martin Gardner revived interest in 1969 with his chapter titled "Flatlands." This resurgence inspired Alexander Keewatin Dewdney, a computer scientist, to delve deeper into the science behind this idea, producing influential publications in 1978 and 1979. Dewdney's "Two-dimensional Science and Technology" meticulously outlined the scientific foundations necessary for a two-dimensional world.

The scientific exploration initiated by Dewdney and popularized by Gardner continues to resonate, illustrating the enduring impact of pioneering ideas.

In this video, "Can Life Exist in 2 Dimensions Instead of 3D? Amazing 2D Life Test!", we explore the potential of life in a flat universe, presenting key concepts from the scientific perspective.

Chapter 2: Principles of the 2-Dimensional World

Dewdney coined the term "Planiverse" for his two-dimensional world, contrasting it with our own, which he dubbed the "Steriverse." He envisioned this universe as a scientifically consistent analogue of our own, potentially existing as a truly flat plane or a slightly thicker surface between frictionless layers.

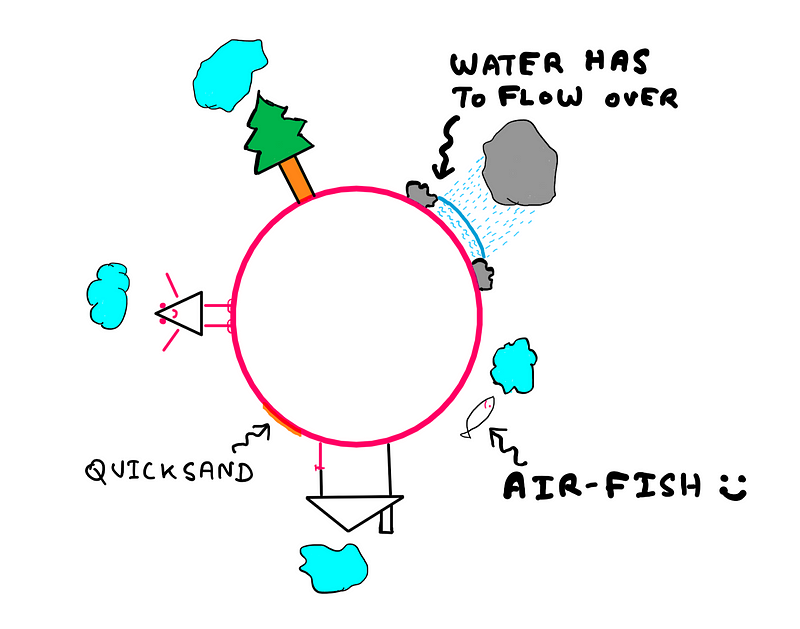

The equivalent of Earth in this two-dimensional setting is named Astria, where inhabitants, referred to as Astrians, can differentiate directions of east-west and up-down, but not north-south.

To establish a robust scientific framework, Dewdney adhered to two guiding principles:

- The Principle of Similarity: This principle states that concepts and states in the Planiverse should closely resemble their counterparts in the Steriverse. For instance, a circle in two dimensions serves as the analogue of a sphere in three dimensions, leading to the circular shape of Astria.

- The Principle of Modification: Here, if conflicting hypotheses arise, the more fundamental hypothesis should be prioritized, with the other modified accordingly. This principle establishes a hierarchy of sciences, ranking physics above chemistry, and chemistry above biology.

With these principles laid out, we can now delve into the implications they have across various scientific domains.

This second video, "Can life exist in 2D? The physics of a 2D Universe," investigates the physical laws that govern a two-dimensional existence, further enriching our understanding of this imaginative concept.

Chapter 3: Physics in the Planiverse

Dewdney conceptualized gravity as a fundamental force within the Planiverse, mirroring its role in our own world. However, he modified the gravitational relationship so that it is inversely proportional to distance rather than the square of the distance, allowing light and other objects to travel in straight lines.

In terms of time, the Planiverse is perceived as a three-dimensional space-time continuum made up of particles analogous to those in our world. Dewdney meticulously derived numerous laws applicable to the Planiverse, including those of thermodynamics, friction, magnetism, and more.

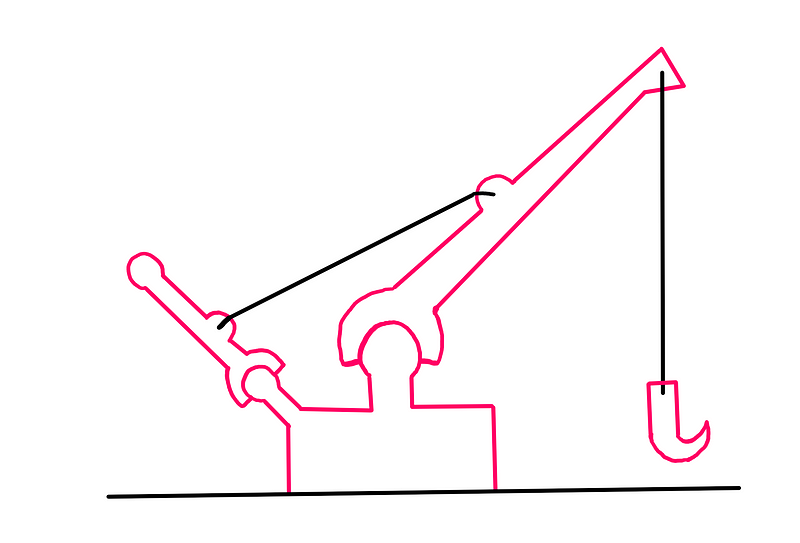

To illustrate these concepts, consider the innovative design of an Astrian hoist featured below:

An engineer from Astria faces unique challenges when designing structures. For instance, she learns from a metallurgist that materials in her world are more prone to fractures, leading her to adjust the dimensions accordingly. Later, a chemist informs her that molecular forces are stronger in the Planiverse, prompting her to revise her designs once again.

Chapter 4: Astronomy and Chemistry in the Planiverse

The Astrian sky presents a semi-circular vista. As the planet rotates around its sun, it experiences day-night cycles, with twinkling stars dotting the night sky. Dewdney determined that stable orbits in the Planiverse would take the shape of perfect circles, posing challenges for complex multi-body orbital calculations.

In terms of chemistry, Dewdney created 16 fundamental elements based on our own chemical laws. Atoms in the Planiverse can form molecules, but intersecting bonds are not permissible, allowing for a unique model of bonding through planar graphs. While the Steriverse allows for 230 distinct crystallographic groups, only 17 exist in the Planiverse.

Chapter 5: Geology and Biology in the Planiverse

Astrian weather parallels that of Earth, with four seasons and varying atmospheric conditions. Notably, rain behaves differently, unable to flow "around" objects, leading to unique geological features and smooth, circular landforms. Dewdney suggests that frequent rainfall could lead to the formation of quicksand.

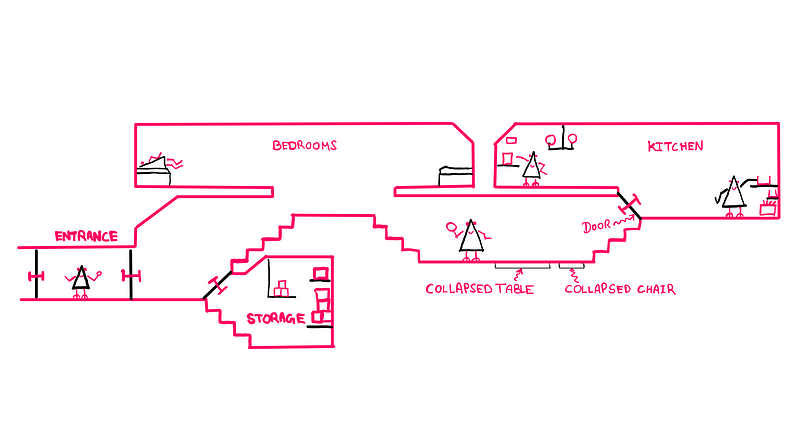

Biologically, Astrian creatures possess cells, bones, and muscles, allowing for various modes of movement. For example, flying does not require wings; instead, an air-foil shape suffices. Dewdney envisioned Astrians as triangular beings with two legs, one arm, and one eye on each side, allowing them to see in multiple directions.

Chapter 6: The Practicalities of Living in a 2-Dimensional World

Living in the Planiverse presents significant challenges due to spatial constraints. With limited dimensions, populations are likely to be lower than in the Steriverse. Astrians must maximize space efficiency; for instance, vehicles must leap over one another rather than passing side by side. Housing is also a challenge, resulting in underground residences equipped with collapsible furniture.

Final Thoughts

The exploration of a scientifically structured two-dimensional world opens up a myriad of possibilities, barely touched upon in this brief overview. The groundbreaking work of Dewdney, Gardner, and others continues to inspire new thoughts and innovations.

In a subsequent essay, I will delve deeper into the practical applications, technologies, and designs that would characterize a two-dimensional existence, along with potential connections to our own three-dimensional reality. Stay tuned for more fascinating insights!

Update: You can read the follow-up essay here.

References and credit: A.K. Dewdney and Martin Gardner.

If you’d like to support my work, consider clapping, following, and subscribing.

Further reading that might interest you: Can You Really Solve This Tricky Rep-Tile Puzzle? and Are We Living In A Simulation?