A Legacy of Science: My Grandfather's Chemical Footprint

Written on

Chapter 1: Remembering MorFar

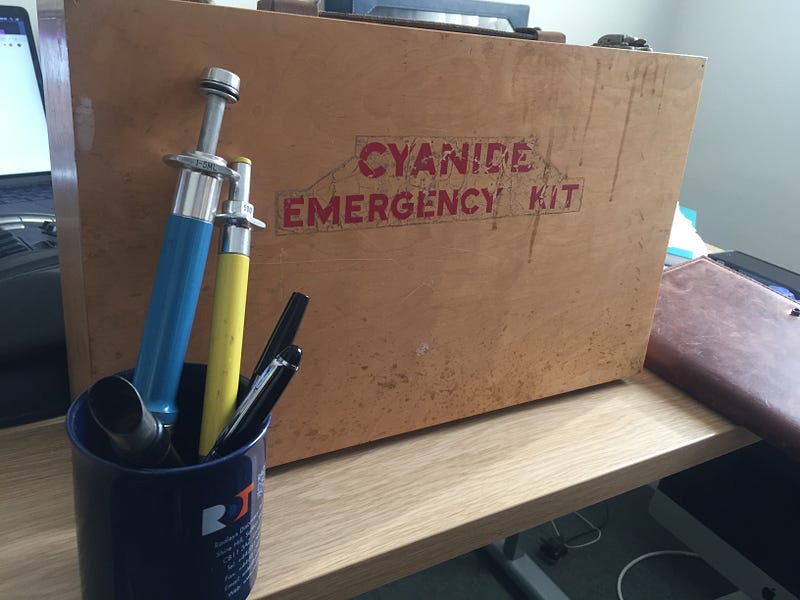

This narrative revolves around the unexpected journey of my grandfather’s pipettes, which now reside in a collection of miscellaneous items on my desk.

The legacy he left behind had the potential for danger, posing risks not only to me but also to my family and neighbors. Yet, every time I reach for a pencil from the mug that shares space with his old lab instruments, I can’t help but feel a mix of respect and nostalgia. Occasionally, when I find myself struggling with writer’s block, I play with these tools, think of him, and often, inspiration strikes.

MorFar was one of my most significant scientific influences. Being Danish, we referred to him as MorFar, which means "mother's father" in Danish. Due to his residence in Copenhagen, our encounters were infrequent, typically once a year. Consequently, my memories of him consist of snapshots from family holidays to Denmark or his visits to us.

A chemist and horticulturist, he was an early advocate of organic food production, long before it gained popularity. He imparted his passion for plants, science, and nature to me.

As a child, he would take me on strolls through the picturesque countryside of the English Home Counties or the vast landscapes of the Baltic coast. We would forage for edible plants along the hedgerows. On occasion, we would find a waterway, crouch by the edge, and observe pond skaters, water boatmen, and daphnia gracefully gliding beneath the surface. We might even capture a few in our lunch boxes to examine under the microscope he would magically produce from his pocket.

His smallholding, which he maintained even after retirement, was a testament to his dedication to research. He crafted unique hybrid plants, and I fondly recall him building a greenhouse entirely from recycled materials, refusing to purchase even a single nail.

However, it was his laboratory, located in an old redbrick outbuilding where he analyzed soil chemical compositions, that truly captivated my imagination. To my ten-year-old self, it felt like a wondrous cave filled with peculiar instruments, bottles, and herbal mysteries.

MorFar loved the theatricality of science. If we behaved well, he would bring out his sodium metal, securely stored in a jar of oil—a relic from a time when safety regulations were not as stringent. He would take it to a quiet spot on his property, use a long pair of forceps to extract a piece of the shiny metal, and toss it into a bucket of water, producing an explosive reaction that would leave us in awe.

Perhaps you've witnessed such demonstrations in school or on YouTube; MorFar's performances were unmatched.

These experiences instilled in me a passion for science, showcasing the wonders it holds and the joy of sharing that knowledge with others. Fast forward a few years, I now hold a PhD in biochemistry and work as a researcher at Goethe University in Frankfurt.

As time passed, I saw him less frequently, making the anticipation of a rare Anglo-Danish family gathering all the more exciting. Upon arriving at my parents' garden, I spotted him lying beside the pond. Fearing he had collapsed, I hurried over, only to find him captivated by something in the water. There he was, sprawled on the grass, peering intently at the life bustling just inches away. I joined him on the damp earth, just as I had done many years before.

By this time, MorFar's health had declined, and he struggled to maintain his smallholding, yet his passion for the natural world remained unwavering. He found ways to continue his research, even moving his laboratory from the smallholding to his apartment.

The last time I saw him was that weekend by the pond. The following weekend, I learned about the extent of his makeshift research station during his funeral. I joined my family to clear out his four-room apartment in a high-rise in Copenhagen. Stepping inside, I was taken aback; the space resembled a bizarre fusion of a home and a scene from a 1960s B-movie about a mad scientist. The kitchen surfaces were cluttered with pH meters, hot plates, pipettes, and oddly labeled bottles alongside standard appliances. The balcony resembled a verdant greenhouse, while the living room overflowed with shelves filled with bottles, jars, and canisters of chemicals.

This was clearly no ordinary clearing-out process.

My family, however, approached it without caution, eagerly opening bottles and dumping their contents down the kitchen sink. When I cautioned against this, they shrugged off my concerns, convinced MorFar had labeled any hazardous materials. A quick inspection of the kitchen dispelled that notion, prompting me to intervene decisively.

Within a day, I categorized the materials into three groups: Category 1, mostly harmless (salts and buffers); Category 2, definitely hazardous (concentrated acids); and Category 3, the "What on earth is this?" items.

Among the latter was a five-liter jar filled with a clear oil and approximately one kilogram of white, crusty cubes. Opening it released a potent petroleum scent, triggering a long-buried memory—it was the very jar of sodium metal we had played with as children. Over time, a thick oxide crust had formed around the soft metal.

Yet, the sodium was not the most concerning item; the real danger lay in the solutions of potassium cyanide. He had previously used it for fumigating greenhouses—pour a little in a dish, add acid, and leave. I shuddered to think about what could happen if the cyanide mixed with acids in the plumbing, potentially releasing cyanide gas throughout the apartment.

Faced with a collection of chemicals that could stock a decent lab, many of which would require extensive risk assessments and emergency kits if used in my university lab, I pondered how to dispose of them. Suggestions ranged from slipping some into MorFar's casket to tossing the sodium into the sea.

Ultimately, I spent the next week carefully transporting the assortment of bottles and jars to a bemused but helpful chemistry department at Copenhagen University for proper disposal.

Afterward, once the hazardous materials were cleared, the clothes were sorted for donation, and furniture distributed among family members, I noticed a pocket microscope and a pair of pipettes sitting on an otherwise bare kitchen countertop. I slipped them into my pocket, a small yet significant connection to my grandfather’s legacy.

Chapter 2: The Art of Restoration

The first video illustrates a meticulous process for restoring antique hardware, highlighting the techniques and tools that can breathe new life into old items.

The second video showcases the effective cleaning of a monument using D/2 Biological Solution, demonstrating the importance of preserving history while being mindful of the environment.