Are Humans Naturally Omnivorous? Exploring Our Dietary Evolution

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Our Dietary Roots

It's time for a confession: I am a pescatarian (gasp). Seven years ago, I stopped consuming meat, and since then, I've navigated the sea of vegetarian and vegan information, both good and misleading. While some resources provide valuable insights into sustainable dietary changes, others are sensationalized and often inaccurate.

Recently, I encountered a particularly frustrating claim stating that humans are evolutionarily herbivores. This assertion set off alarm bells in my mind. Armed with some background knowledge and a strong cup of coffee, I decided to delve into the question: Are humans inherently vegetarian?

Here's what I found:

More Than Meets the Eye

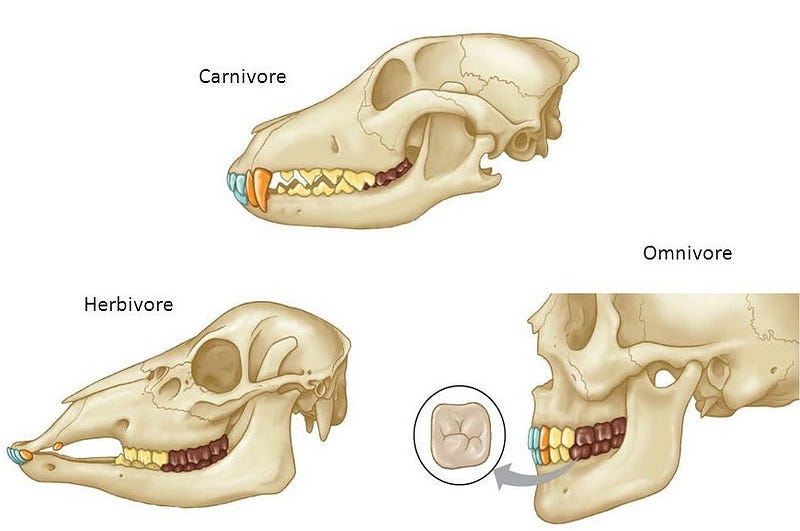

To determine a species' diet, one of the most straightforward methods is to examine their teeth. These unique structures are designed to efficiently process the types of food an animal consumes. Some researchers even suggest that tooth morphology may reveal dietary habits more reliably than analyzing stomach contents.

In summary, carnivorous animals possess long, sharp front teeth for seizing and tearing their prey, complemented by blade-like molars for slicing meat. Conversely, herbivores are equipped with chisel-shaped incisors for gnawing and flat molars for grinding plant material.

When we examine human dentition, we find that our teeth are somewhat intermediate between those of herbivores and carnivores. Our front teeth aren't as effective at tearing flesh as a carnivore's canines, nor are our molars as adept at grinding as those of herbivores. However, we are capable of performing both functions.

Digestive Design

Beyond tooth shape, the entire digestive system provides insight into dietary habits. Typically, carnivores have simpler digestive processes and shorter digestive tracts, often with less distinct organs.

For humans, our digestive tract length lies between that of herbivores and carnivores. While it is shorter than that of herbivores, it is longer than that of carnivores. Moreover, our digestive system is more complex than those of large felines or other predators, despite lacking multiple stomachs like some herbivores.

The Family Connection

Another significant factor in determining diet is evolutionary relationships. Animals that are closely related often share similar dietary preferences. To understand our dietary evolution, we can look to our distant relatives.

In the primate order, to which we belong, omnivorous diets are the norm. Unlike many other mammalian groups with specialized diets, primates tend to have varied food preferences. While most primates favor fruits and plant materials, many also consume birds, eggs, small animals, and insects.

Focusing on our close relatives in the Hominidae family, we see a diverse dietary pattern:

- Gibbons: Fruits, plants, eggs, and insects

- Orangutans: Fruits, plants, eggs, insects, and small vertebrates

- Gorillas: Fruits, plants, and insects

- Bonobos: Fruits, plants, insects, and fish

- Chimpanzees: Fruits, plants, nuts, eggs, insects, and vertebrates

This variety indicates that our physiology is adapted to handle a wide range of nutritional sources.

Addressing the Cooking Debate

An interesting argument I've encountered suggests that humans are more susceptible to illness from raw meat compared to predators.

It's worth noting that meat consumption does carry risks for all animals, including predators, which frequently contract diseases from their diets. The trade-off here is that meat provides high rewards for those capable of digesting it.

Humans can digest raw meat, as evidenced by the popularity of dishes like sushi and steak tartare. However, the increased frequency of illness from raw meat consumption among humans can be attributed to two factors: the risk increases as meat spoils, and generalist eaters like us are not as specialized in digesting meat as carnivores.

Conclusion

Humans are biologically equipped to consume meat, and we are indeed a generalist species capable of thriving on a diverse array of diets. Therefore, the ideal diet for you may not involve completely eliminating meat.

However, it’s crucial to note that while our bodies can process meat, all our relatives typically use it as a supplementary food rather than a staple. Our craving for meat is akin to cravings for sugar and salt—indicating an evolutionary adaptation to seek out hard-to-find nutrients. In the modern world, especially in the U.S., meat consumption often far exceeds what is necessary for health.

On average, Americans consume approximately double the recommended amount of meat, which can lead to various health issues, including an increased risk of cancers, diabetes, high cholesterol, and heart disease.

Instead of making drastic dietary changes, consider implementing small, sustainable modifications. Always consult a healthcare professional for personalized advice rather than relying on random online sources.

Have a science question? I’d love to explore it with you! Feel free to ask in the comments, and I'll address it in a future article!

Chapter 2: The Omnivorous Nature of Humans

This video discusses whether humans are true meat eaters or if we fit better into the herbivore or omnivore categories, providing an engaging lecture on veganism.

This video examines the dietary classifications of humans—are we omnivores, carnivores, or herbivores? It offers a comprehensive analysis of our dietary evolution.